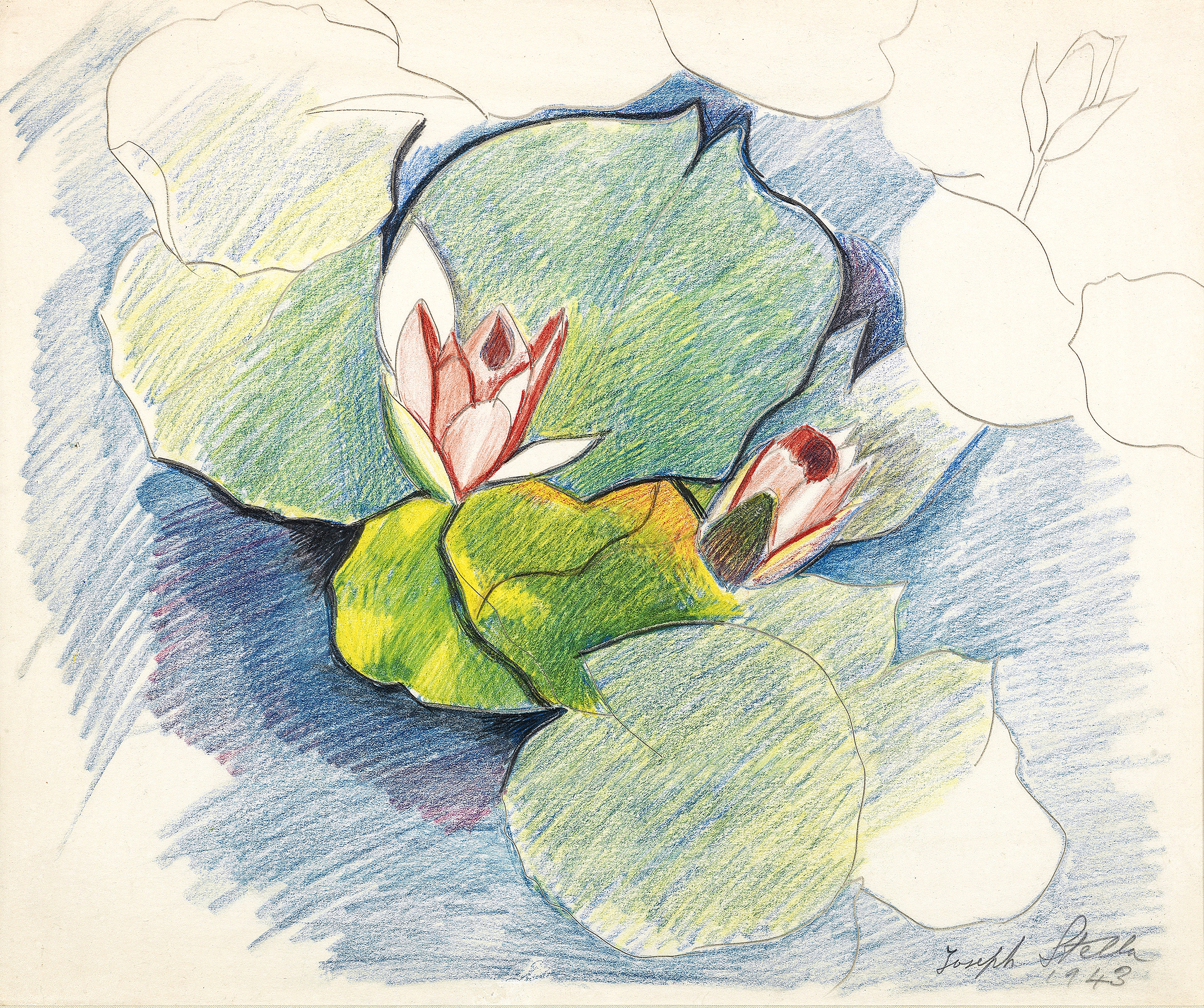

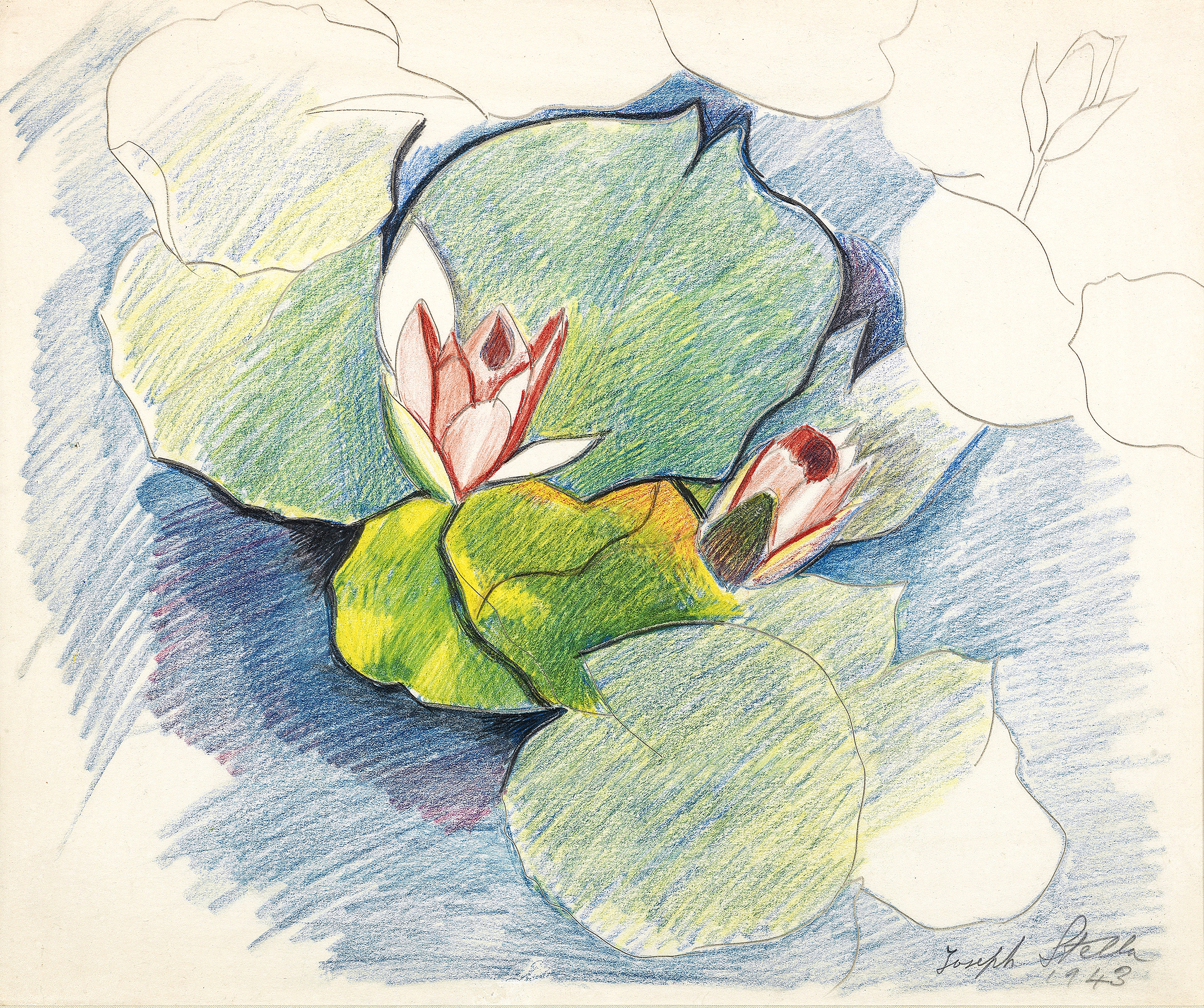

“Two Pink Water Lilies,” 1943, silverpoint and crayon on paper, 11 by 12 1/2 inches. Collection of B. Dirr. Digital image courtesy of the Brandywine River Museum of Art.

By Kristin Nord

CHADDS FORD, PENN. — Joseph Stella has long been identified as a Futurist painter whose paintings of the Brooklyn Bridge and Coney Island earned him early renown. But there was a dramatically different Stella, an Italian immigrant who arrived in 1896 enamored of the poetry of Walt Whitman and an avowed nature lover.

Now, in “Joseph Stella: Visionary Nature,” at the Brandywine Museum of Art, we encounter this lyrical pantheist executing virtuosic works across media. The show, co-curated by Stephanie Heydt, PhD, Margaret and Terry Stent curator of American Art at the High Museum of Art, and Audrey Lewis, PhD, the Brandywine’s associate curator, on view through September 23, is a feast for the eyes and the spirit.

The impetus for the show, according to Brandywine director, Thomas Padon, came from a chance encounter with Stella’s epic 84-by-76-inch “Tree of My Life” at the home of Seattle collectors. After discovering that the High Museum of Art in Atlanta owned “Purissima” (1927) in its permanent collection, the two museums teamed up to mount a traveling exhibition. It opened first at the Norton Museum of Art in Boca Raton, Fla., and then moved to the High before landing here at its final stop. It has been nearly 40 years since Stella’s last exhibition and is the first devoted to his nature works.

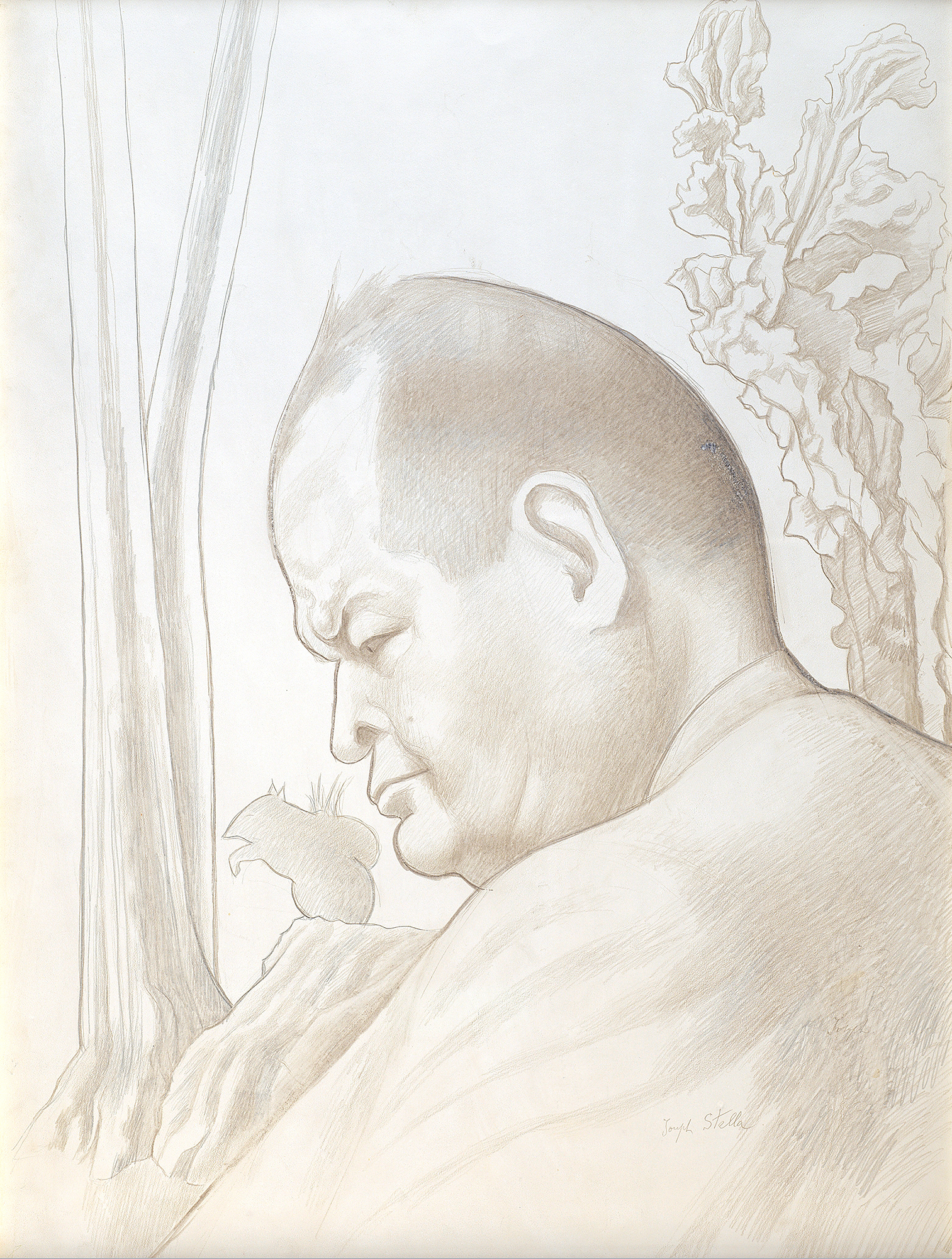

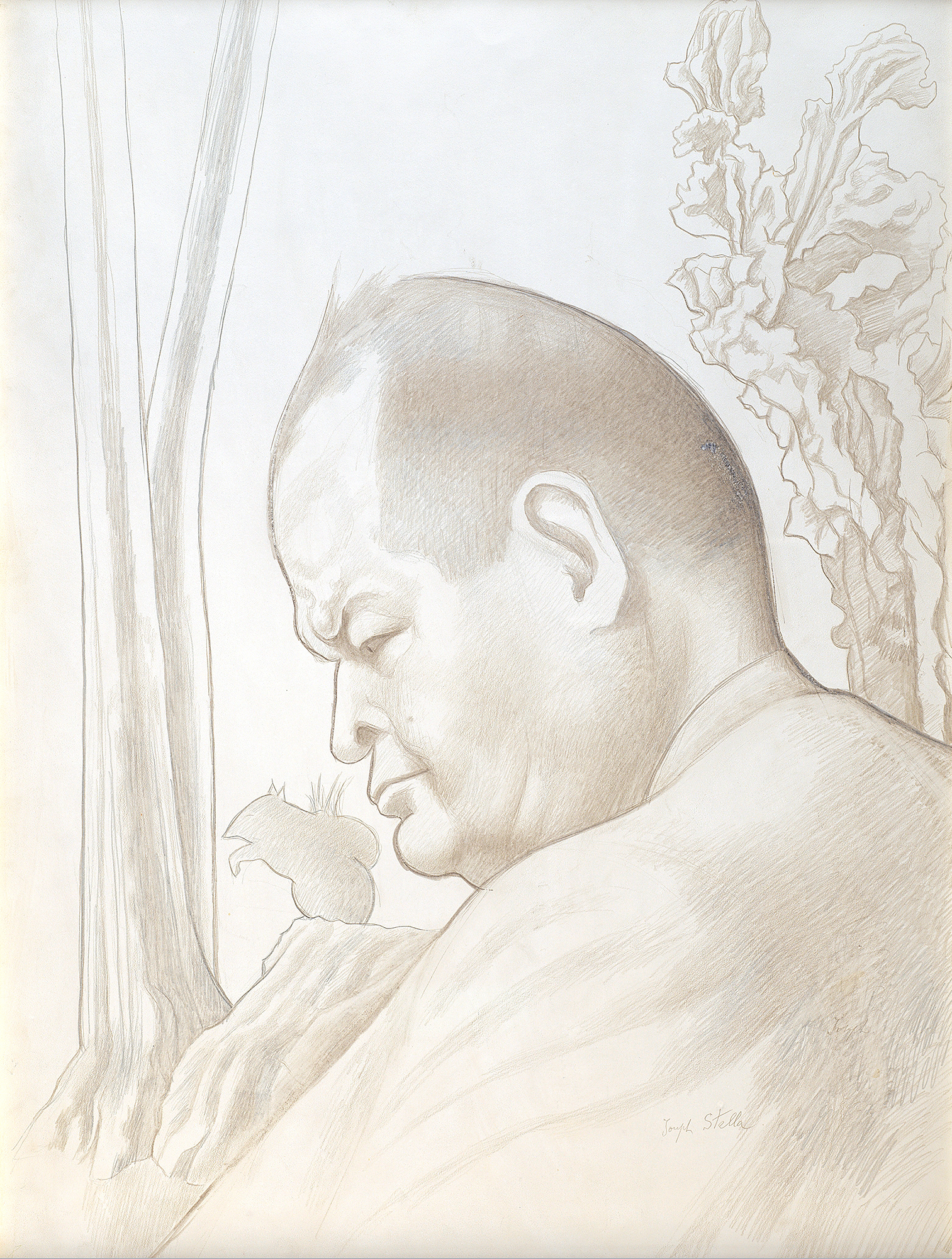

“Self-Portrait,” 1920s, metalpoint with graphite pencil on wove paper prepared with white ground on paper, 30-3/16 by 22-3/16 inches. Philadelphia Museum of Art, purchased with the Alice Newton Osborn Fund, the Katharine Levin Farrell Fund, the Margaretta S. Hinchman Fund, the Joseph E. Temple Fund, and with funds contributed by Marion Boulton Stroud and Jay R. Massey, 1988. Digital image courtesy of Philadelphia Museum of Art.

“Making sense of Stella required a disregard of conventional categories, as he fit into none of them neatly,” The New York Times arts critic Hilton Kramer observed. “Stella was at once a modernist and a traditionalist, a futurist who worshipped at the shrine of the Old Masters, and an artist with a passion for the romance of Industrial America who constantly fled to more venerable and exotic locales.”

Stella was born in 1877 in Murano Lucano, Italy, a remote medieval mountain town southeast of Naples. He entered New York at Ellis Island with initial plans to study medicine and join his older brother, Antonio’s, practice in Little Italy. But his brother recognized Joseph’s artistic talents and urged him to alter his career path. Stella studied briefly at the Art Students League and then with the American Impressionist William Merritt Chase. He was already a highly skilled draftsman, and his earliest success came with his highly detailed drawings of working-class people in his own immigrant community.

On a trip to Paris in 1911, where Fauvism, Cubism and Futurism were in vogue, he encountered Matisse, Modigliani and Picasso, as well as Futurists Carlo Carrà, Umberto Boccioni and Gino Severini. Over the next few years, he would experiment, and exhibit two works in the International Exhibition of Modern Art at the 69th Regiment Armory in New York. With the unveiling of “Battle of Lights,” “Mardi Gras,” “Coney Island” and “Brooklyn Bridge,” the latter was acclaimed as a Futurist masterpiece.

But even as these paintings were garnering attention at the Bourgeois Gallery in Manhattan, the artist was recalibrating. By 1919, he had turned away from more industrial subjects to focus on the powerful spiritual connection he felt with the natural world.

Untitled, circa 1918, collage on paper (leaf and paper mounted to paper), 7 3/4 by 7-5/8 inches. Kraushaar Galleries, New York. Digital image courtesy of Kraushaar Galleries, New York.

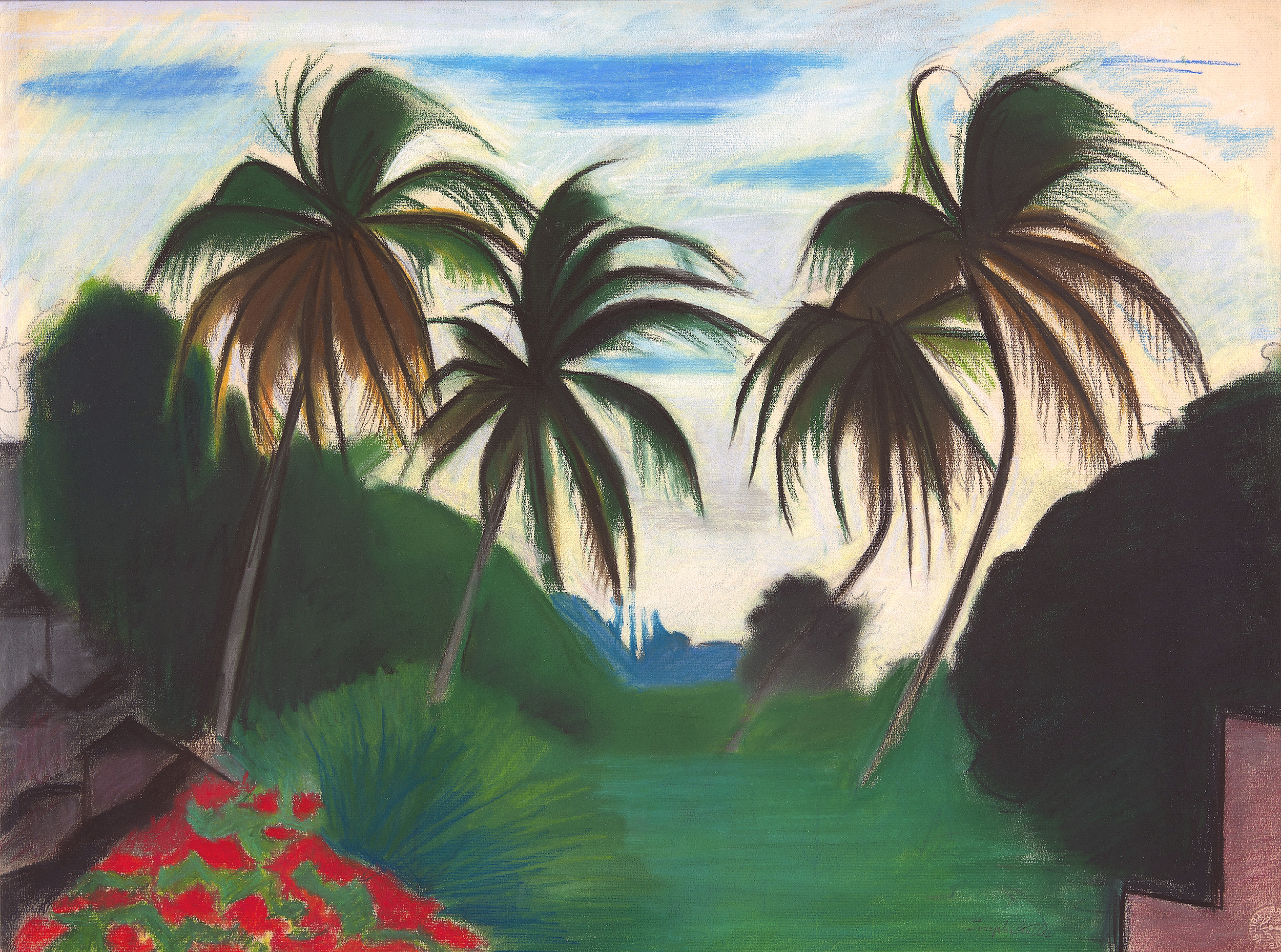

Stella was homesick for southern Italy and would return there many times. He said he was inspired by “modernity, archaism, industry and nature all at once,” and refueled creatively with side trips to Paris, North Africa and Barbados as well. But, his eclecticism increasingly puzzled both the art critics and the public. And on a personal level, his friend, the composer Edgar Varèse confessed, “You never knew how he would be. He was in some ways so refined, so delicate — and then he could be so vulgar, obscene. And physically, too, he was a paradox – big, fat, heavy-bodied, and yet so graceful. What beautiful hand gestures he had.”

The art historian Barbara Rose agreed, writing in her exhibition catalog for a 1998 exhibit at Eaton Fine Art in West Palm Beach, Fla., Joseph Stella: Flora, that there was nothing straight forward about Stella, whose “stylistic shifts are as violent and disruptive as his mood swings. His volatile personality, shaped by two distinct cultures — his native Italy and his adopted America — was as contradictory, dualistic and intense as his art.”

“Over a lifetime he would move from academic realist to Orphic colorist to avant-garde Futurist to Precisionist, Cubist Realist to experimental Dada collagist to visionary landscape painter. Through it all, the single thread uniting it all was “the suggestive and symbolically loaded flower image.”

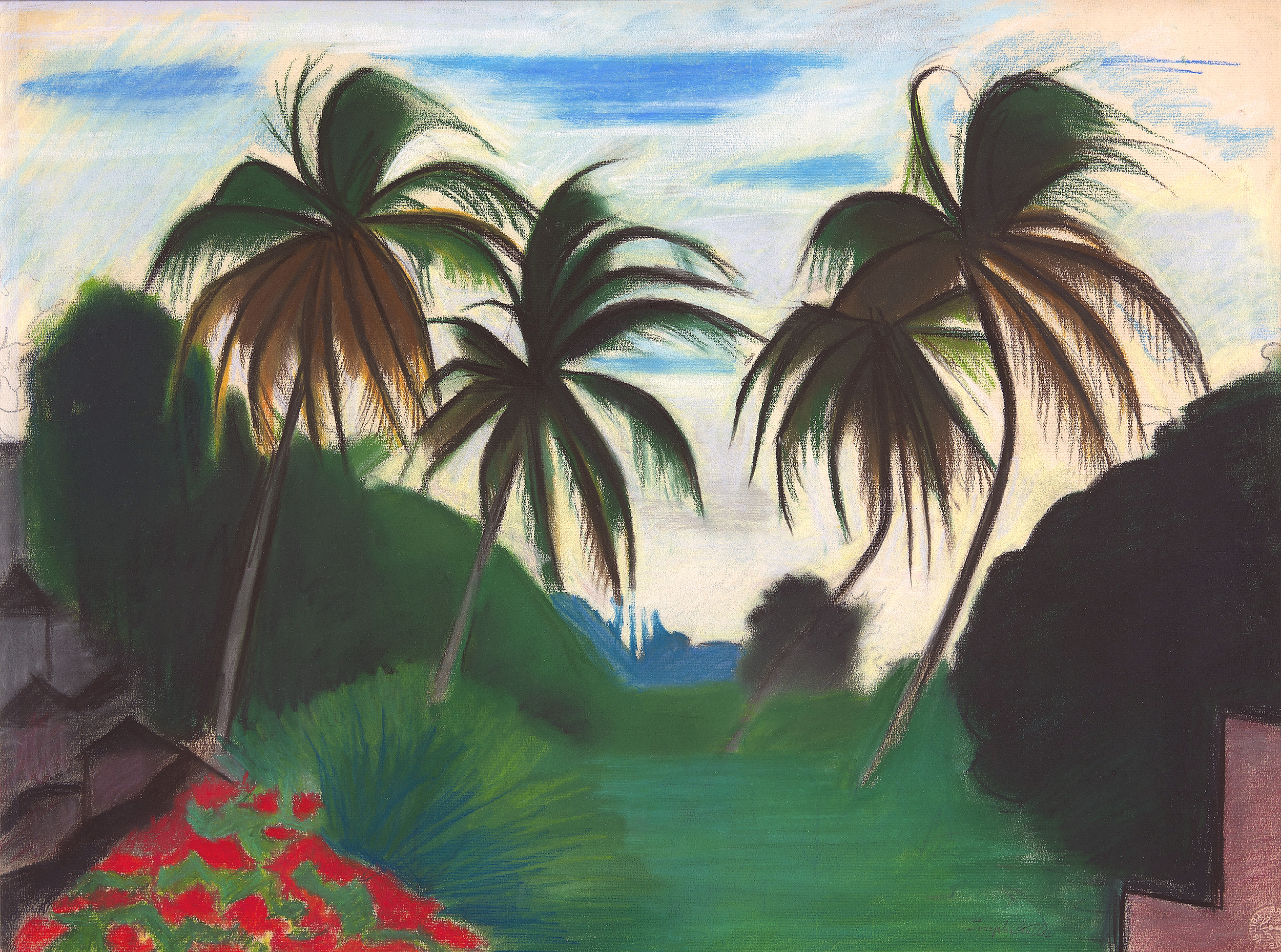

“Barbados,” circa. 1938, pastel on paper, 18 1/4 by 25 inches. Collection of Dr. and Mrs. Gene Arum. Photo by David Almeida.

In the 80 works on display, viewers experience his stylistic shifts and experiments. There are poignant landscapes in pastel and oil paintings that appear to have been culled from antiquity. There are abstract scenes presumably from his childhood, myriad botanical sketches, portraits, folk art Madonnas, paintings on glass, and collages. And there is his epic “Tree of My Life,” his brilliant riposte to Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself.”

Anti-immigrant sentiment had been running high in New York at this time, and practicing Catholics and Italians ranked low on the social hierarchy, Heydt notes. Though Stella had long ago rejected the teachings of the Catholic Church, he remained deeply inspired by its devotional iconography. After visits home in 1923 and 1926, he increasingly mined the mythical and spiritual traditions of his Italian heritage. Unlike the dark palette of his abstract urban works, his new paintings were all about color, light and simplicity of expression.

“The Virgin,” 1926, oil on canvas, 39-11/16 by 38 3/4 inches. Brooklyn Museum, gift of Adolph Lewisohn, 28. Digital image © Brooklyn Museum.

Karli Wurzelbacher, PhD, curator at the Heckscher Museum, and a contributor to the exhibition’s catalog, reported on the artist’s field trips to the New York Botanical Garden (NYBG) on reconnaissance.

“While most of his modernist peers avoided addressing nature in their art or fled urban centers in search of nature pristine and untouched, Stella looked to nature within the city.” He lived for years in an apartment just minutes away, and the NYBG became his observational laboratory. There was flora and fauna from all over the world, and the managed natural site “catalyzed Stella’s renderings of plants while binding them to the modern city.” For an artist who had written that his most fervent wish was “that my every working day might begin and end, as a good omen, with the light gay painting of a flower,” NYBG conservatory was manna from heaven.

As early as 1919, Stella had begun working in silverpoint, a centuries-old technique in which a silver-tipped stylus is pulled across treated paper. Stella mastered the technique and used it to make botanical drawings “of old master quality,” Heydt said. He produced many botanical sketches, but also several remarkable self-portraits, as well as one of his friend, Marcel Duchamp.

What Stella found and sketched, remembered or imagined was all grist for his mill. He mixed hothouse species with flowers inspired by his travels, and he sometimes injected plants and fruits he encountered at the neighborhood market as well. Crotons, lilies, lotuses, cranes, songbirds, swans and herons recur in his works, quite often against a backdrop of beloved landmarks from his childhood — a smoldering Mount Vesuvius, the blue Bay of Naples and the profile of Capri.

“Flowers, Italy,” circa 1930, oil on canvas, 74 3/4 by 74 3/4 inches. Phoenix Art Museum, Ariz., gift of Mr. and Mrs. Jonathan Marshall, 1964. Digital image © Phoenix Art Museum. All rights reserved. Ken Howie photo.

“Flowers, Italy” (1930) overflows with flowers and birds nestled within a setting evoking Gothic architecture. Nature reigns as well in “Purissima” (1927) a massive painting in which the near life-size Madonna is part-Christian icon and part pantheistic-goddess.

Of the work “Red Flower” (1929), owned for a time by Duchamp, The New York Times critic Edward Alden Jewell marveled at the artist’s ability “to make color glow through dark opaque forms.”

“Lyre Bird” (circa 1925) which upon a first encounter appears to depict a mythical specimen is, in fact, his rendering of a rare Australian songbird that was on the endangered list at the turn of the century. The Lyre bird’s plight had aroused great interest in the early 1900s and it had been featured in many scientific publications. Stella also created about a dozen reverse glass paintings, including “The Water Lily” (circa 1924) at a time when the Botanical Garden was in the headlines for its colorful cross-fertilized lilies.

“Purissima” stands nearly life size and is among Stella’s most striking in his series of folk art Madonnas. The figure is reminiscent of the effigies, often adorned with flowers and fruit, that lead religious processions during the liturgical year.

“Purissima,” 1927, oil on canvas, 76 by 57 inches. High Museum of Art, Atlanta, purchase with funds from Harriet and Elliott Goldstein and High Museum of Art Enhancement Fund, Photo by James Schoomaker / Courtesy of High Museum of Art.

“I thank the Lord,” he wrote, “for having had the good fortune to be born in a mountain village. Light and space are the two most essential elements of painting, and my eager art took its first flights there in that free, light-filled radiant space.”

While Stella received respectful reviews at his final solo show in 1939 at the Newark Art Museum, sales were tepid. In the final years of his life, as his health declined, he was forced to retreat from the NYBG to his studio. But even then, his friend, the artist Charmion von Wiegand, reported a visit to Stella’s studio was an event. In one such visit he found the artist “in the center of the room serenely unconscious of confusion and putting the last touches on the svelte curves of a tulip.” Flower studies of all kinds fallen to the floor and transformed the studio “into a growing garden.”

During the artist’s lifetime and since critics and scholars have attempted to parse the tremendous variety in Stella’s oeuvre, Wurzelbacher believes New York Botanical served as the bridge that Stella disparate interests to intermingle and flourish.

“Joseph Stella: Visionary Nature” is on view at the Brandywine Museum of Art through September 24.

The Brandywine Museum of Art is at 1 Hoffman’s Mill Road. For additional information, 610-388-2700 or www.brandywine.org.